Uncovering Philly law enforcement's secret bank accounts

On a chilly night in 2014, Nassir Geiger left his house an innocent man with a 2000 Buick LeSabre and $580 cash in his pocket – his paycheck for the week. He drove to a nearby McDonald’s for a late-night snack. But by the time he returned home the next morning, Philadelphia police would have taken all that away.

“I was scared,” Geiger recalled. “I had never been to jail before.”

Geiger’s only “crime” had been seeing a familiar face in the parking lot of the Northeast Philly McDonald's. As he paused to say hello to a coworker from the city’s Streets Department, he drew the attention of undercover narcotics police. Two plainclothes officers, suspecting the harmless interaction had been a drug deal, followed Geiger on his way home. Brandishing their firearms, they charged his car. After the stop, Geiger watched helplessly as one officer confiscated his wages, while another hopped into his Buick and sped away.

There were no drugs to be found. Geiger, a longtime sanitation worker with no criminal record, would never be charged with a crime. But thanks to the city’s controversial civil asset forfeiture program, he would go to jail for the night and leave, the next morning, penniless and on foot.

In the name of furthering narcotics investigations, civil asset forfeiture allows Philadelphia police to seize millions in cash, cars and homes each year from ordinary citizens, even in cases where charges are never sought. But what happens to these assets after they're seized – and liquidated into secretive municipal bank accounts – remains one of the biggest mysteries in Philadelphia law enforcement.

For more than two decades, the District Attorney’s Office has refused to disclose – even to City Council members – exactly what it does with the millions in sometimes-ill-gotten gains confiscated through civil asset forfeiture. But now, long-hidden financial documents obtained through a Right-to-Know request filed by City&State PA and Philadelphia Weekly outlined nearly $7 million in secretive expenditures, spanning the past five years.

The records depict a slush fund for DA and police spending that runs the gamut from the mundane to the downright bizarre, all enabled by laws that empower police to seize property from individuals sometimes merely suspected of criminal activity. In one instance, the forfeiture “bank” helped top off the salary of a former DA staffer who once served as campaign manager to now-jailed former District Attorney Seth Williams. (The office maintains these expenses were appropriate and eventually reimbursed.) Other forfeiture dollars paid for at least one contract that appears to have violated city ethics guidelines – construction work awarded to a company linked to one of the DA’s own staff detectives. (The DAO said it is now conducting an “internal investigation” into these payments.)

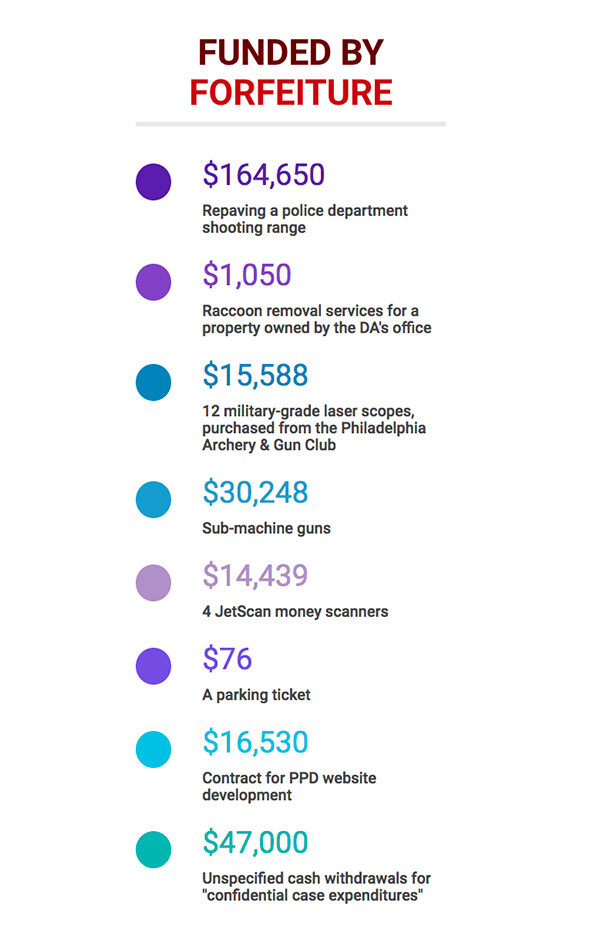

With little need to concern itself with public scrutiny, the DAO’s clandestine revenue stream also paid for much more: $30,000 worth of submachine guns (equipped with military-grade laser sights valued at $15,000) for police tactical units; a $16,000 website development contract; custom uniform embroidery; a $76 parking ticket; $1,000 in raccoon-removal services; a push lawn mower; a pair of outboard motors; and tens of thousands in mysterious cash withdrawals – along with thousands of other expenses.

While the DAO liquidates many of the assets it seizes, other records obtained by City&State PA and Philly Weekly also revealed that the office has long loaned out forfeited cars to its office personnel. Cars – not unlike Geiger’s seized Buick – are routinely doled out to top deputies either for work use, as take-home cars or, in at least one case, as playthings for the district attorney himself. These perks are in addition to those that staff already enjoy, like dedicated downtown parking spots, free gas and repair work – all courtesy of Philadelphia taxpayers.

Yet even this unprecedented disclosure appears to represent only a fraction of the city’s civil asset forfeiture proceeds. In reports submitted annually to the Pennsylvania attorney general, the DAO previously claimed to have spent anywhere from $2 million and $7 million in forfeiture funds each year – at least $5 million more in total spending than what is shown in the budget documents delivered to City&State PA and Philly Weekly. Officials declined to explain the multimillion-dollar discrepancy, despite multiple inquiries.

Innocent victims of the forfeiture machine are often forced to pursue a complex legal process just to win back their own property – and few have the resources or wherewithal to bother. In the pursuit to reclaim his vehicle, Geiger ended up joining six other victims in a class-action suit against the city with the help of the libertarian Institute for Justice.

Attorneys at the Virginia-based nonprofit depict civil asset forfeiture as one of the greatest threats to property rights in the nation today. But, under the Trump administration, Attorney General Jeff Sessions has sought to expand the practice’s already widespread use. In 2014, federal authorities notoriously seized $5 billion – more than was reported stolen in burglaries nationwide, according to a report from the Institute for Justice. Meanwhile, big cities like Philadelphia continue to cultivate their own forfeiture juggernauts with limited outside scrutiny.

As part of a potentially historic settlement with plaintiffs in the IJ lawsuit, city lawyers have offered to radically restructure forfeiture spending to support drug treatment programs over law enforcement spending. Yet critics still doubt that the DAO or police can be trusted to administer the current, opaque bank accounts at all.

“There is no democratic check on how law enforcement uses forfeiture funds, and no oversight by any politically accountable body. The current law places very few restrictions on how they can use that money,” said Molly Tack-Hooper, of the Pennsylvania ACLU. “Every aspect of this is troubling. Law enforcement has tremendous power in our society. At a minimum, we deserve to know how they’re using their resources.”

The Ouroboros Budget

Even top city administrators who oversee key aspects of the Philadelphia District Attorney and Police Department’s budgets have long been kept in the dark about the forfeiture budget. The DA’s office alone holds the purse strings to this discrete fund, which many sources said was informally divded with the PPD as a “60/40" split – Finance documents show that, in practice, police get far less: about 27 percent of forfeiture revenues.

Asked by City Council during 2016 budget hearings to describe the nature of city forfeiture revenues, then-DA Williams pointedly declined to answer.

“The Forfeiture Act of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania really prohibits the District Attorney from sharing with municipal funders what those totals are, out of the fear that municipal governments will de-fund prosecutors and law enforcement across the state for that,” he said.

It’s a dubious statement, Tack-Hooper says today.

“There is definitely nothing in PA's forfeiture law – either the new version or the previous version – that requires DAs to keep their forfeiture practices or revenues secret,” she said.

There is, however, a statute dictating that revenue is only to be used for drug enforcement, community policing efforts, witness relocation and blight mitigation.

A great deal of money does appear to be spent on investigative costs: evidence baggies, wiretapping expenses, hundreds of thousands in cell phone and internet bills for staffers. Yet in numerous other instances, expense records suggest the Philadelphia DAO bent the limits of these terms and then covered its tracks to seem compliant with threadbare regulations. Virtually none of the forfeiture income was ever used to fund "softer" approved uses like drug treatment or crime prevention programs, according to its own annual reports.

“There is a need for community policing, for drug treatment programs, for safe injection sites. But they weren’t spending it on any of that – they were spending it on machine guns and lawnmowers," said Democratic DA candidate Larry Krasner, a longtime critic of asset forfeiture. "They were spending it on military-style weaponry in a department that should be less militarized.”

Krasner has said that, if elected, he would hand over forfeiture proceeds directly to the city’s general fund.

Because current revenues exist outside of the city budgeting process, forfeiture expenditures evade the city’s typical contracting guidelines. While DAO officials insisted there is a “multi-step approval process for all goods and services purchased with civil asset forfeiture funds,” they could not provide any other details about that process.

Meanwhile, that vetting process appeared flimsy enough that, in one case, a salaried DA staffer’s construction company was able to obtain one of these contracts, a violation of city ethical guidelines.

Due to its controversial seizure of people’s homes, the DAO has become a major property owner, spending about $184,000 to maintain or seal its extensive real estate portfolio. One of the building contractors paid to perform that work, NorthEast Construction Inc., is owned by April Slobodrian, the wife of DA staff detective Joseph Slobodrian – despite city employees being barred from benefiting, directly or indirectly, from city contracting.

Joseph Slobodrian joined the DAO in 2012, after spending many years stationed in North Philadelphia’s drug-plagued 25th Police District. Since then, his wife’s company has won at least $14,000 worth of home repair contracts for properties managed by the DAO’s forfeiture unit. On Slobodrian’s own online resume, he lists himself as a manager at NorthEast Construction.

He did not respond to a request for comment, although a relative acknowledged Slobodrian’s involvement with both the DAO and NorthEast Construction.

Sources said many of the contracts paid through the forfeiture account date back decades, even to former DA Lynne Abraham’s tenure, and a DA spokesperson confirmed that contracts with Slobodrian’s company date back to his time in the 25th District.

“In light of your suggestion that he ‘serves as a manager at Northeast Construction LLC,’ we are now conducting an internal investigation to see if that is true, and if it is, we will take the appropriate action,” DA spokesman Cameron Kline said.

However, the Mayor’s Office, the police department and the DAO declined to answer specific questions about other unvetted contractors paid through forfeiture accounts. Citing the ongoing class-action lawsuit filed by Geiger and others, the city offered only praise for the oversight purportedly enforced by the two prime beneficiaries of forfeited assets.

“Expenditures made during the timeframe you asked about involved a system of checks and balances between the police department and the District Attorney's Office,” said Andrew Richman, chief of staff for the city solicitor. “Part of this oversight included making sure that expenditures made from the narcotics account had a nexus to narcotics enforcement.”

Exactly how much was spent on actual narcotics work remains unclear. Officials also offered no explanation as to why numerous expenses – such as $160,000 used to repave the police department’s gun range – came out of unmonitored forfeiture accounts rather than the city’s general fund.

Yet, from a broader perspective, spending from these accounts resembles an ouroboros – a snake eating its own tail – as almost half the money brought in seems to have been funneled back toward costs associated with the forfeiture program itself.

Some $2.2 million was paid in salaries between 2012 and 2016 – scarcely enough to cover the annual cost of the nine attorneys who staffed the DA’s two forfeiture offices during those years. $217,000 went to car repairs or to maintain or seal the properties it has seized over the years. Another $192,000 went to other law enforcement agencies that assisted with drug raids. Some $120,000 was spent to lease a garage on State Road for the storage of seized but yet-to-be-auctioned vehicles. More than $14,000 was used for cash-counting machines to bundle street money. A suburban courier company called MedEx Logistics was paid $70,000 out of forfeiture accounts to handle related subpoena services – notifying people that their property was being seized by law enforcement. Some $30,000 went to internal “audits.”

Still more was paid to Barry Slosberg and Company, an auction house that helps liquidate some of the private property seized by the DA. It billed anywhere from $5,000 to $15,000 monthly for unspecified “advertising costs.”

“When forfeited property is sold at auction, there are also advertising costs associated with the auction. The amounts vary as the need and frequency of advertisements in the Philadelphia media market varies,” Kline said, explaining the wild shifts in ad costs.

The Campaign Manager

Forfeiture accounts also paid large sums in the form of a salary for lawyer Bryan Lentz between 2011 and 2013. A former state representative and respected attorney specializing in white-collar crime, Lentz had managed Williams’ failed 2004 campaign for the office and remained a loyal supporter throughout the now-disgraced former DA’s political ascent.

That relationship may have prompted Williams to select Lentz to fill a lingering vacancy at the city’s Regional Gun Violence Task Force in late 2011. Similar task forces across the state are funded by the state attorney general and administered by county DAs, with the aim of sweeping illegal guns off the streets.

But, for reasons that are still unclear, Williams directed his finance department to cover Lentz’s salary with money from the forfeiture account – some $275,000 over approximately a year and a half, paid through untaxed biweekly checks that were stamped “Drug Forfeiture Account.”

Lentz says he didn’t know where the paychecks were coming from and could not recall his exact salary.

“I don’t why they chose to pay us that way,” Lentz said, reached over the phone at his law office. “I received the checks, but I didn’t pay the bills (for the task force). I believe the arrangement was that they would use that money and get reimbursed by the AG.”

The DAO affirmed Lentz’s salary was later reimbursed. Joe Grace, a spokesperson for Attorney General Josh Shapiro, noted that the DA is permitted to exercise its own discretion in how to pay for these personnel costs before submitting receipts for reimbursement.

The DAO also refused to explain why Lentz was compensated in such a manner, but Kline insisted a predecessor had been similarly compensated with forfeiture money.

However, no other task force employee has since been paid in a similar fashion or as generously. The current task force head, criminal prosecutor Caroline Keating-McGlynn, earns $102,000 annually.

The Company Car

While some DA employees were, in essence, being paid out of accounts flush with money picked off purported drug dealers, other staffers were repurposing seized vehicles as de facto company cars.

Vehicle logs, expense records and emails show staff and top deputies at the DAO routinely drove vehicles confiscated through civil asset forfeiture proceedings, with associated maintenance costs similarly covered with forfeiture cash. The cars also enjoyed taxpayer-funded gas from municipal refueling stations and assigned private parking spots at the DA’s downtown garage.

Former DA Lynne Abraham and Republican DA candidate Beth Grossman, herself a 21-year ADA who used once oversaw the DA’s forfeiture unit, both acknowledged the long-running practice.

“The statute permits it – the cars can be used. But the rule of thumb is that they must be used for official purposes only,” Grossman said.

The DAO refused to answer any questions about the use of seized vehicles. A spokesperson said only that the office “does not comment on internal personnel issues.”

Advocates for the reform of civil-asset forfeiture said that, even when legal, the use of these vehicles for routine office functions was abhorrent. Like all forfeiture cases, cars may have been seized before their owners have been convicted of any crime – like Geiger’s Buick.

“As described, it’s an outrageous practice,” said state Sen. Daylin Leach, who has sponsored legislation to reform forfeiture practices across the state. “But the bigger issue is that civil asset forfeiture inherently lends itself to this sort of abuse.”

The DAO confiscated 72 vehicles in 2014, nearly all of which ultimately headed to auction. But about 22 other vehicles confiscated through forfeiture over the years were pressed into use by the DAO, according to city fleet records. A roster showed many of the forfeited cars are sedans of older make, although the registry also includes several late-model SUVs and two pickup trucks.

The DAO refused to release documents outlining which staff used the cars or for what purpose, citing security concerns. But inter-office emails obtained through a right-to-know request captured one exchange between former deputy Tariq El-Shabazz concerning his use of a seized 2012 Toyota Tundra. In that exchange, the former deputy emailed the office to request that the city fix a flat tire he detected while driving the pickup truck home, on a weekend. A spokesperson for El-Shabazz said he needed 24/7 access to a vehicle to respond to the site of police-involved shootings, per new protocols he'd helped establish.

The police department said there were no police-involved shootings during the month he reported the flat tire.

Receipts from a forfeiture account also depict ADA Mark Gilson routinely bringing forfeited cars in for maintenance. An ally of Williams, Gilson was assigned to the office’s Conviction Review Unit under El-Shabazz. Williams and members of his security detail are also recorded billing forfeiture accounts for assorted car maintenance costs, along with car washes and wax jobs.

A high-level source in the DAO stated it was a long-standing “tradition” for the first assistant and other top officials to have constant access to a vehicle, forfeited or otherwise. But the use of the vehicles was clearly widespread: fuel logs show other forfeited vehicles consumed 2,200 gallons of fuel at municipal gas stations between August 2016 and February 2017.

It is worth noting that, in addition to these forfeiture vehicles, the DAO also has access to a fleet of conventional city-owned cars, as well as a massive rental-car budget that racked up more than $660,000 in leasing expenses from forfeiture accounts over five years.

Former DA Lynne Abraham defended the practice of having a flexible supplement of forfeited cars, saying vehicles critical to casework were sometimes tough to come by for tasks like transporting traumatized victims or hesitant witnesses or attending community meetings.

“But I don’t know what anyone would need a truck for,” Abraham said, referring to El-Shabazz’s use of the Tundra. “Was he moving?”

Internally, some sources stated that Williams had, at times, attempted to rein in the too-casual use of forfeited vehicles during his tenure, apparently softening his stance in the years leading up to his indictment on felony corruption charges. But among the dozens of wide-ranging charges leveled against Williams, federal prosecutors said the DA had himself misused grants intended for the High-Intensity Drug Trafficking Program to acquire vehicles for personal use.

These abuses seem to extend to forfeited vehicles as well. Several former DA officials recalled, in 2011, that Williams had ordered the repurposing of a forfeited Harley-Davidson motorcycle – Even emblazoned the bike with a license plate reading “DA-2,” according to Grossman.

She recalled Williams asking Chief of County Detectives and former highway patrolman Chris Werner to give him riding lessons so he could participate in the Hero Thrill Show, an annual police motorcycle rally and fundraiser.

Grossman, then head of the forfeiture office, said she objected to the frivolous use of a forfeited bike at the time.

“I don’t know if Seth Williams ever rode it or not, but eventually the motorcycle was auctioned off,” Grossman recalled.

He didn’t, according to Jimmy Binns, a lawyer who organizes the Thrill Show. The license plate was pried off the bike and later given to Grossman. The DAO auctioned the Harley the following year.

The War on Forfeiture

The expenses traced here from the city’s forfeiture accounts shed light on but one corner of the vast, shadowy apparatus that is the forfeiture program.

In a mandatory, one-page financial report submitted to the state attorney general for fiscal year 2012 – a bare-bones form of transparency – the DAO reported spending $7.3 million in forfeiture proceeds. But expense records from the two forfeiture accounts reviewed in this investigation - it remains unclear if there are additional accounts used to maintain the program - only account for roughly $1.5 million in spending during that year. There were similarly gaping discrepancies in reports for the following years.

The Mayor’s Office, the Law Department and the DAO all declined to offer an explanation for those discrepancies – once again citing the ongoing lawsuit.

Robert Frommer, an attorney representing Nassir Geiger at the Institute for Justice, noted the city has long safeguarded forfeiture expense documents from the eyes of outsiders. Frommer’s team has been seeking discovery of forfeiture expense reports through the lawsuit, but did not obtain the expense records until presented with them by reporters.

This summer, Geiger sat at an outdoor café and recounted the Kafkaesque experience of spending months trying to reclaim his cash and car from police custody. While he learned he was not the only falsely accused individual fighting back, he also emphasized that if he hadn’t found pro bono legal representation, he might have joined the majority of those who gave up on recovering their stolen possessions.

“In Philadelphia, the overwhelming majority of people who have their property seized give up on trying to get it back,” Frommer said. “Even if they’ve done nothing wrong, it’s simply not worth it. That’s why we’re involved.”

According to a 2012 City Paper investigation, about 90 percent of people who have had their property taken away abandon their reclamation efforts during the first stage of the forfeiture process.

But Geiger did, eventually, get his car back – albeit years later and minus some $500 in storage fees. He says it was a point of pride for him.

As for the $580 in cash he lost that night in 2014, he was never made whole, and assumes his money long ago made its way into the forfeiture coffers, never to be seen again.

As his lawsuit continues to unfold, concerns surrounding the city’s forfeiture program have become a recurring theme of the Philadelphia DA’s race. Democrat Larry Krasner has vowed to end the program altogether, while Republican Beth Grossman remains defensive of her former office, pointing out the program allows law enforcement to get dirty money off the street, while quickly seizing and sealing drug houses.

“The forfeiture act remains on the books and has never been declared unconstitutional. It has been used as a tool to prevent drug dealers from ruining neighborhoods,” she said. “What gets lost is the impact a drug house can have on a neighborhood. It decreases property values and quality of life. However, if elected, I’m open to looking at all ways of evaluating the forfeiture process.”

The Republican also distanced herself from actual spending decisions made while she worked at the DAO.

“I never had any decision-making authority or otherwise participated in how that money was spent,” she said. “The forfeiture statute as written does provide for funds to be used in crime-fighting and community initiatives. Those are the proper uses for the funds I would like to see, if I get elected.”

But her opponent, Krasner, said there were no “proper” use of the funds under the current system.

“She’s trying to make the issue whether there should be forfeiture at all. But the issue is whether you want to forfeit assets from poor people who haven't done anything – and if that money should then be dumped into a slush fund,” he said. “It's a giant conflict and it’s almost unavoidable that you’re going to have people who are motivated and biased to take things they shouldn’t be taking, and will be rewarded for doing so. It’s the only area where law enforcement gets to keep what they kill. It’s almost unavoidable that you’re going to dicey expenditures.”

Krasner said Grossman herself was to blame.

“The bottom line is: it all happened on her watch,” he emphasized. “This is what she did.”

Interestingly, the issue has also found bipartisan resistance in Washington. In a stunning move, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives recently approved an amendment that would stymie Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ proposed expansion of the federal government’s asset forfeiture program.

If successful, the class-action suit Geiger is involved in could very well change the way the Philadelphia handles asset forfeiture and, tellingly, the plaintiffs are not seeking damages or compensation for their life-changing encounters with the city’s forfeiture machine. For Geiger, a law-abiding family man, the damage has already been done - he just wants the system to change. He worries about his children running into police.

“My daughter is starting to drive,” he says. “I don’t want her to get pulled over and get harassed by cops, or have them take stuff from her just because they can.”