Housing

Whistling past the political graveyards

The Mother and Twins monument at Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery. Photo courtesy Small Bones

Philadelphia isn’t just the birthplace of our nation – it’s also the burial place of many of our Founding Fathers and other political notables. Here are but a few of the resting places of the state’s famous figures.

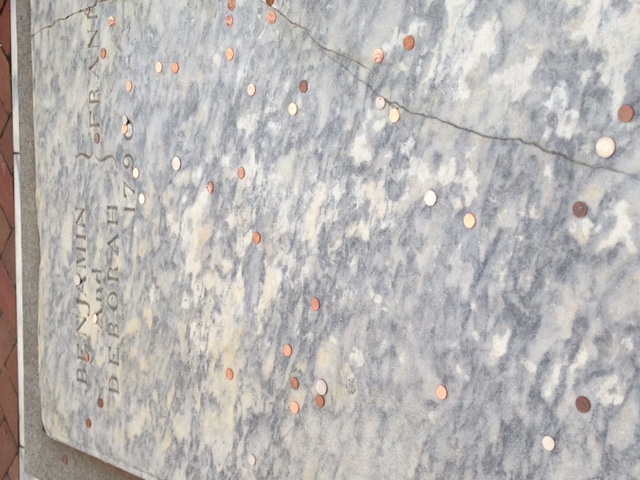

Ben Franklin’s grave is daily showered with pennies in a misinterpreted tribute to his maxim, “A penny saved is a penny earned.” - Terri Akman

Established in 1719, as many as 4,000 souls are buried in Philadelphia’s Christ Church Burial Ground in Old City, though only 1,400 stones remain today. Five signers of the Declaration of Independence are among the many prominent early American leaders interred here.

• Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) Probably the most famous Philadelphian, Franklin was a scientist, philosopher, printer, diplomat, inventor and signer of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. His grave is easy to spot: It’s usually covered in pennies, a symbol of good luck and perhaps a nod to his famous motto, “A penny saved is a penny earned.” A crack discovered in his marker is soon to be repaired. What is it about historical artifacts

in Philly that crack?

• Dr. Benjamin Rush (1746-1813) It’s likely that Rush would have a lot to say about this year’s election – he passionately championed many of the same issues, like health care, immigration, supporting the military and the death penalty (which he opposed). Also a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Rush was a physician known as “The Father of American Psychiatry,” a social reformer, treasurer of the United States Mint and founder of Dickinson College.

• Sarah Franklin Bache (1737-1808) Daughter of Benjamin and Deborah Franklin, she shared her father’s passion for our country. Her contribution to the cause was helping to create The Ladies Association of Philadelphia, a leading source of funds during the Revolutionary War. She solicited donations door-to-door, bought fabric and created uniforms, and provided other needed supplies to the Continental Army.

• John Dunlap (1747-1812) Printer of the Declaration of Independence, he published the first successful daily newspaper in the United States, the North American and United States Gazette. Though John Adams declared July 2 as the date to celebrate the country’s independence, by the time Dunlap printed it, it was July 4. And the rest is history.

Located in Philadelphia’s East Falls neighborhood, Laurel Hill Cemetery has more than 33,000 monuments and over 11,000 family lots within its Schuylkill River-bordered confines. Founded in 1836, thousands of 19th- and 20th-century marble and granite funerary monuments and elaborately sculpted hillside tombs and mausoleums fill Laurel Hill’s 78 acres. In a time before public parks and museums, the multipurpose cultural attraction gave the general public a glimpse of the art and refinement that typically had been only for the wealthy. Among those buried there:

• Lewis Charles Levin (1808-1860) Leader of the anti-immigrant Know Nothing party and an anti-Catholic social activist, Levin’s monument was a long time coming. “After he died, his fans bought a lot at the top of the hill for a large and imposing monument, but the treasurer ran off with the money, so for decades, the cemetery had a large base with nothing on it,” said guide Michael Brooks.

• Bernard Goodheart (1931-2014) Known as the judge who played Cupid, the appropriately named Goodheart married hundreds of couples in his City Hall courtroom each Valentine’s Day for decades. While on the bench, he resolved a city-crippling transit strike and threw out an $11 million libel suit filed by former Mayor Frank L. Rizzo against the weekly newspaper Welcomat.

• Charles Thomson (1729-1824) Emigrating to the British colonies in America from Ireland in 1739, he became a leader of Philadelphia’s Sons of Liberty and served as secretary of the Continental Congress throughout its existence. After 14 years in a cemetery at Harriton, the promoters of Laurel Hill asked his heirs to move his body to the new cemetery. When grave robbers at Harriton threw the bodies they were robbing in a cart to make a hasty retreat, the bones were reinterred in Laurel Hill. Some say not all of his bones made the move.

• Boies Penrose (1860-1921) The longest-serving Pennsylvania senator until 2005, when his record was surpassed by Arlen Specter, Penrose was a boss of the city’s Republican machine. “He once summed his philosophy to a group of businessmen, saying, ‘I believe in the division of labor: You send us to Congress, we pass laws under which you make money, and out of your profits you further contribute to our campaign funds to send us back again to pass more laws to enable you to make more

money,’” said Brooks.

Photo by Terri Akman

Betsy Ross (1752-1836) Widely credited with making the first American flag, Ross is now interred in the Betsy Ross House courtyard, after being moved from the Mt. Moriah cemetery for the Bicentennial. While she is known as a seamstress, in fact, this proto-patriot successfully operated an upholstery and flag-making business.

A national historic shrine, Old City’s Mikveh Israel Cemetery, founded in 1740, is the oldest tangible evidence of Jewish communal life in Philadelphia. Soldiers from the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812 and the Civil War are buried there, including:

• Nathan Levy (1704-1753) When his infant tragically died, Levy appealed to William Penn’s son, Thomas, chief of the Proprietary Government of Pennsylvania, for a private place to bury his child. That led to the establishment of the Mikveh Israel Cemetery. The owner of several merchant ships, Levy used one of his ships, the Myrtilla, to bring the Liberty Bell from London to Philadelphia

in 1752.

• Haym Salomon (1740-1785) A financial broker, Salomon provided a reported $650,000 of his own money – over $17 million in today’s dollars – when General George Washington needed cash to pay his soldiers during the Revolutionary War. Even after the war, he is credited with raising money to bail out the debt-ridden government.

Dating back to 1761, the markers in St. Peter’s Church Graveyard in Philadelphia’s Society Hill neighborhood are a mix of obelisks, broken columns, pyramids and pedestals with urns, many worn almost completely away. Among the notable Revolutionary War figures and national politicians are:

• Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844) President of the Second Bank of the United States, credited with bringing the classical revival style to Philadelphia in choosing architect William Strickland to design the Second Bank on Chestnut Street in the style of a Greek temple.

• Stephen Decatur (1779-1820) He first defeated the Barbary pirates in 1804 by burning the USS Philadelphia, which had run aground in Tripoli, thus keeping it out of enemy hands. By the War of 1812, he was a commodore and negotiated peace with the Barbary pirates. Killed in 1820 in a duel, Decatur was buried in Washington, D.C., but his remains were moved to his family’s plot at St. Peter’s in 1846.

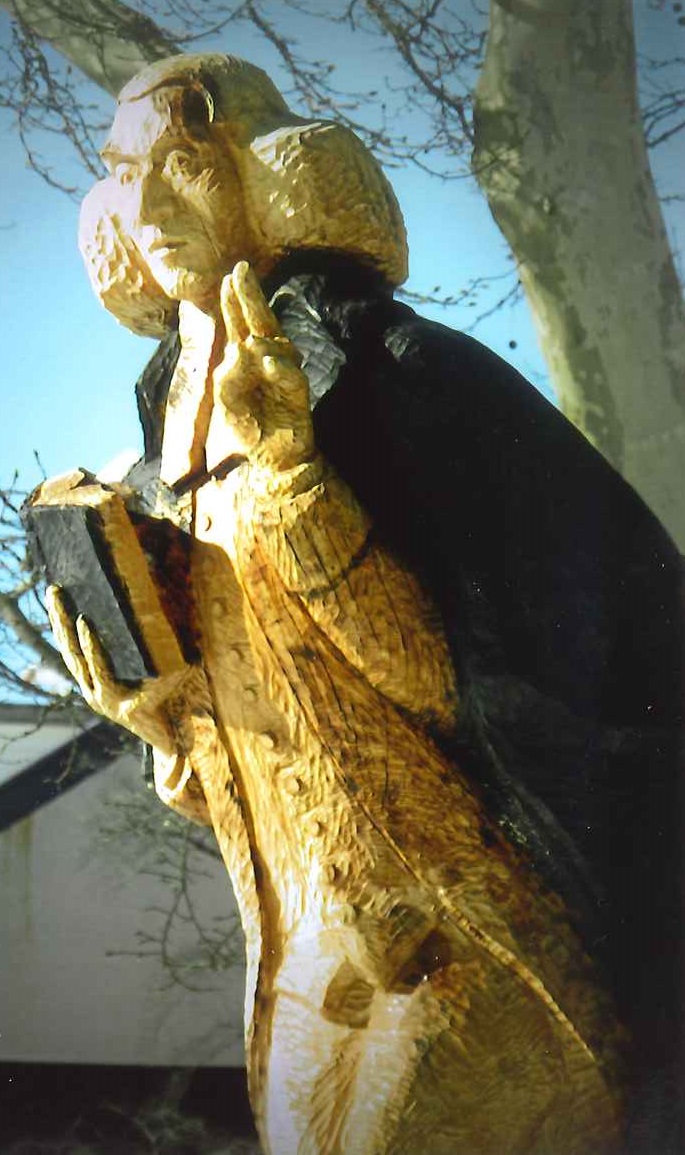

One of the most famous – and striking – memorials at Old Pine Street Church is this 14-foot likeness of the Patriot Pastor, George Duffield. Photo by Terri Akman

Old Pine Street Church’s crowded graveyard, a block from St. Peter’s, dates back to 1764. It holds between 4,000 and 5,000 souls in wooden caskets stacked three-deep, at 9-, 6- and 3-foot depths in an area less than three-quarters of an acre. Among those buried:

• George Duffield (1732-1790) Co-Chaplain of the Continental Congress, a 14-foot likeness of the Patriot Pastor, carved from a maple tree, appears to be preaching to the Revolutionary War soldiers buried in the graveyard. Duffield’s body, entombed in a lead coffin, is the only intramural burial inside the Colonial-era church. Numerous renovations caused his gravestone to be moved three times but never his body, which still rests below the floor in the church’s mail room.

• Jared Ingersoll (1749-1822) Son of a Loyalist father who was tarred and feathered for being a Stamp Tax Collector, Ingersoll was an ardent proponent of constitutional reform. He attended every meeting of the Constitutional Committee, though he was known as “the man who was silent.” A signer of the Constitution, he went on to become a famous attorney, trying one of the first labor cases in the country. Since he died on Oct. 31, this is a fitting time to pay your respects.

Students from Fulton Elementary School, next to Shreiner Cemetery, often help with cleanups there, including the memorial to Thaddeus Stevens.

Established In 1836 on what was then the outskirts of the city, Lancaster’s Shreiner-Concord Cemetery was opened to the public for burials with no restrictions on race or religion. The small, park-like cemetery holds the remains of about 350 souls, including 40 known veterans of military service, mostly from the Civil War. As members of the Shreiner family passed away or moved on, the cemetery eventually declined into its current status of an “orphaned property.” With the aid of the community, the cemetery continues to remain open as a wooded passive park, though burials are no longer accepted. Those interred include:

• Thaddeus Stevens (1792-1868) Hailed as the father of the 14th Amendment, which granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including former slaves recently freed, Congressman Stevens would be closely following current events were he alive today. He was also a champion of education, describing his greatest accomplishment as preserving free public schools in Pennsylvania.

• Jonathan Sweeney (1832-1915) Buried alongside his wife, Anna Eliza, at the foot of Stevens’ grave, Sweeney was a member of the U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War. He is also believed to have been active with the Underground Railroad, secretly helping slaves on Southern plantations flee from bondage into the free state of Pennsylvania and points

farther north.

The Heinz mausoleum at Pittsburgh’s Homewood Cemetery. Photo: Christopher Bailey

Part of the American Cemetery Movement of the 1800s, Pittsburgh’s Homewood Cemetery, a lawn park-style cemetery established in 1878 on 200 acres, is just about a third full with 78,000 graves. Major restorations and more than a century of informed management has maintained the greenswards and deep vistas of the cemetery’s design. Notable features of the cemetery include the Art Deco/Tudor Gothic office and chapel, wrought iron gates by Samuel Yellin and over 250 private mausoleums, including a 35-foot pyramid. Among those buried:

• H. John Heinz III (1938-1991) Heinz served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1971-77, then as a U.S. senator from 1977 until his untimely death in an airplane crash. The Republican worked to protect Social Security and health care benefits for the elderly, insure free and fair trade, and was committed to the environment. He rests in his family’s dome-roofed mausoleum, among four generations of his family, 27 different people, in the crypt below.

• Perle Mesta (1889-1975) Known as the “hostess with the mostest,” Mesta spent most of her life in Washington, D.C., as a “kingmaker,” supporting politicians she believed in. She threw elaborate parties and was the inspiration for Irving Berlin’s musical, “Call Me Madam,” where she was portrayed by Ethel Merman. An early supporter of Harry S. Truman, she received the ambassadorship to Luxembourg. ■