Economic Development

Improving economic development in PA continues to face hurdles

Everyone – Republicans, Democrats, the private sector – agrees it’s crucial to the stature’s short-term and long-term success. But there is precious little agreement on how to make it happen.

The Hoover-Mason Trestle, built on a reclaimed industrial steel manufacturing site in the Lehigh Valley. Alex Potemkin via Getty Images

In poll after poll, Americans have made it clear that the economy is yet again atop their list of concerns going into the presidential election. The same could be said of state lawmakers and business leaders, who continue to work on creating a more business-friendly environment, increasing productivity and raising revenues – all while battling challenges like years of population decline, uncertain trendlines, workforce training shortfalls – and, occasionally, each other.

Despite Pennsylvania being one of the country’s most economically productive states, ranking sixth among states with the highest GDP, policymakers and business leaders are at odds over what they think is needed to boost the state’s economy and to stand out from other states as the race continues to find and train the next generation of workers for jobs both extant and to come.

Commonwealth crystal ball

Experts say that part of what will help Pennsylvania succeed is leveraging a mix of the old and the new – like promoting manufacturing while embracing and incorporating innovative advancements.

“All we can do is look back in the past and see what happened – that’s where you look at some of the heavy advancements in manufacturing through the late ’90s and early 2000s as some of the robots and the computers got smaller and faster, and automation was able to happen at a faster clip,” Carl Mararra, executive director of the Pennsylvania Manufacturers’ Association, told City & State.

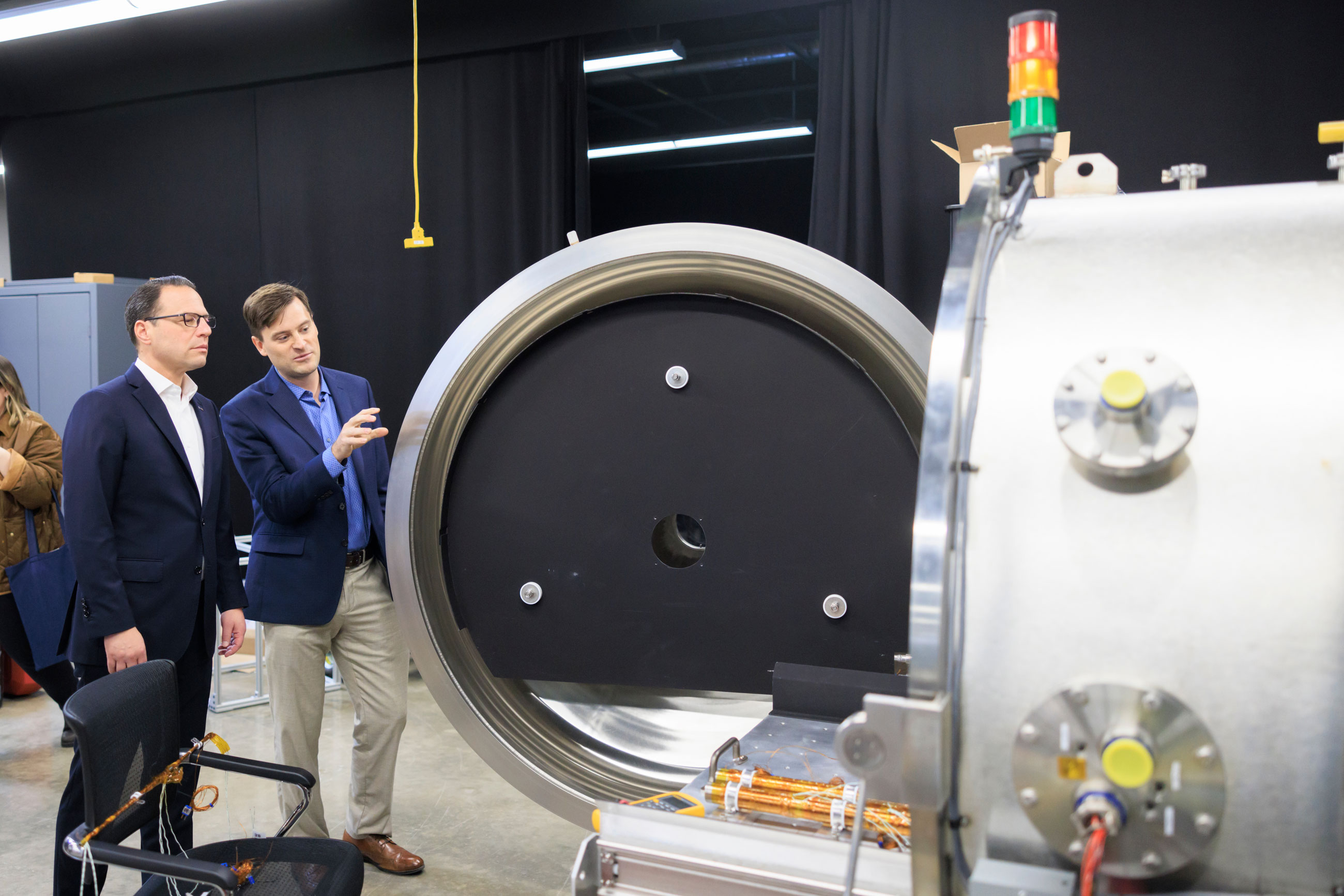

Policymakers have sought to put Pennsylvania on a positive track toward the future, including Gov. Josh Shapiro, who introduced a 10-year economic development strategy earlier this year.

Shapiro said the plan will focus on five key goals: investing in economic growth to compete, continuing to make government work at the speed of business, opening doors of opportunity to all Pennsylvanians, innovating to win, and building vibrant and resilient regions.

Shapiro and Department of Community and Economic Development Secretary Rick Siger announced the 10-year plan at OraSure Technologies in the Lehigh Valley, a region Siger said exemplifies the commonwealth’s economic capabilities.

“It has an incredibly powerful manufacturing base, it has found ways to takeadvantage of its exceptional proximity to East Coast markets, which is something that is inherent in its place, but they’ve done a good job of taking care of it. And it’s a place that you don’t always think of as an innovation capital, but actually is,” Siger told City & State. “It has great research universities. It has the heritage of the semiconductor industry in Bell Labs and is taking really deliberate steps to move that forward.”

Inhibited innovation

Republicans in Harrisburg have long sought to eliminate what they’ve called the “PA startup penalty” – a tax provision that allows businesses to carry net operating losses forward and deduct them from future profits that’s been capped for startup firms and those in industries like manufacturing. (Pennsylvania and New Hampshire are the only two states that cap deductions below the federal limit of 80% of taxable income.)

Kenneth Louie, an economics professor at Pennsylvania State University and director of the Economic Research Institute of Erie, told City & State that growth in the future will stem from the partnerships developed between the public and private sectors, along with the state’s higher education institutions.

“We already have an outstanding backbone or infrastructure, where we have some of the world-class universities that are conducting some of the state-of-the-art research in high-tech,” Louie said. “But the irony or the paradox is, the state hasn’t been able to convert that world-class research into broader outcomes like job growth and greater prosperity across the state.”

Mararra said innovators coming out of schools such as Carnegie Mellon or Drexel University are smart enough to see whether a state’s business climate is best to begin and grow a company in.

“They have (an) idea and they want to make a business out of it, so they’re going to do 10-year projections on what the business model for that investment looks like. And when they see that Pennsylvania is only going to cap their losses of 40% in those 10 years where they’re making the most significant amount of investment, they’re gonna take a step back and then look elsewhere,” Mararra said.

A group of state House Republicans introduced a bill package in March aimed at boosting startups within the Keystone State. Among the bills is legislation introduced by state Rep. Valerie Gaydos, an Allegheny County Republican, that seeks to provide uncapped and non-expiring operating loss deductions to in-state startups.

“New business creation is a large part of building our future,” said Gaydos. “The more we can do to fuel innovation and innovative companies, the better our futures will be. However, many new companies operate at a loss in the first few years,” Gaydos said in a statement following the bill’s introduction. “By extending the net operating loss carry forward tax deduction both in the amount that can be deducted and the length of time in which one can take the deduction against future gains, Pennsylvania can be competitive with other states.”

Alex Halper, senior vice president of government affairs with the Pennsylvania Chamber of Business and Industry, told City & State the state must do more to give “employers and entrepreneurs and innovators reasons to come to Pennsylvania and stay in Pennsylvania for the long term.”

“We need a foundational strong business climate that incentivizes employers and those industries to grow here,” he said. Halper added that aside from creating a business-friendly environment, the commonwealth’s strategic planning requires “taking a long-term view of burgeoning industries and different sectors of the economy that are primed for growth, and being very thoughtful and strategic with how we kind of leverage any public resources to maximize growth in those industries.”

Experts say now is the time for the commonwealth to double down on its institutions and infrastructure to mark its place as an innovation hub. Mark Muro, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, found that while Pennsylvania possesses clear advantages compared to other states in education, research and development, the commonwealth lags competitors when it comes to supporting startups and converting that support into jobs.

“There are clearly opportunities for a state like the commonwealth that has a real history and feel for manufacturing,” Muro told City & State. “It’s about making sure your small-to-medium-sized enterprises don’t get left behind in a new more rigorous competition environment.”

Muro said advanced industries – those driven by innovative technologies – should be central to any forward-looking state strategy.

“Many of (the advanced industries) are manufacturing industries but they’re not commodity manufacturers,” Muro said. “This could be biomanufacturing but it also could be advanced equipment manufacturing, technology manufacturing … These are really important because they have the highest productivity and therefore a high GDP yield per worker.”

Lost in the past

As the state and its leaders turn their focus toward the future, there are also concerns related to ensuring those in fields that may be on the way out aren’t hung out to dry along with any obsolete machinery.

An industry that’s already experienced that turnover is manufacturing, where places like Erie are looking to shift toward more high-tech versions of themselves.

“If you talk to people in Erie … I think you’ll get a sense of optimism that has taken hold … Our manufacturing job base has been declining for many years, but it’s actually somewhat surprisingly held steady recently,” Louie said, noting that adaptation of manufacturing, although it may lead to some job losses, benefits the economy and GDP overall.

“You don’t necessarily want to eliminate overnight, very abruptly, the historical facets of traditional modes of manufacturing. Erie is a very good case – we are still heavily sort of linked to this manufacturing historical past,” Louie said. “The idea is to gradually convert or adapt these traditional manufacturing centers and incentivize them to apply more high-tech-oriented and more advanced processes, methods and modes of operation that will help them to increase the viability, first of all, of their operations … the kinds of jobs that are associated with those kinds of advanced manufacturing, those jobs can be more highly paid.”

Mararra said leaders in the manufacturing sector have already begun utilizing artificial intelligence and automation, and there’s a clear consensus that exploration in the area is only beginning. In a survey shared at the Manufacturing Leadership Council, 22% of its members said they are currently using AI and 57% plan to do so in the next two years. The findings also revealed that 32% of members say AI will have a somewhat significant impact on their production in the near future, and that 96% predict their level of manufacturing AI investment will grow by 2030.

Mararra believes the manufacturing jobs will always be there – the key to ensuring the commonwealth’s future economy and workforce keeps up with demand is to have a workforce being educated and trained in what’s expected to be the jobs of tomorrow.

Muro offered a similar perspective, adding that the state doesn’t have to bring in workers but can instead work on developing them from within the state’s borders.

“I’m not sure it’s a complete mystery what the next necessary skill base is … there’s the possibility of providing basically a broad array of digital skills that then can be topped off at the firm level, given whatever particular set of tools and machines that are being used,” Muro said. “I would not use the word ‘attract’ for workers,” he added. “The state needs to grow them.”